مشروع التخرج (FAB)

3 مشترك

صفحة 1 من اصل 1

مشروع التخرج (FAB)

مشروع التخرج (FAB)

الى ان ابدا بعرض مشروع التخرج أوجة الشكر الى أشرف حسنى على دياب وأحمد السيد جاد الذى قمنا بعمل هذا المشروع

OBJECTIVES :

1. Expectations on FABS.

FABS have to be designed free from national boundaries con'straint to in crease safety and efficiency in Air traffic service provision. the task should be considered in regard to the general functions assigned to FABS.

2. Reviewing competing perspestives on FABS.

A minimalist approch consists of fostering service co - ordination of providers on components of service over cross-border or air space European regions by means of negotiated participation. An embryonic approch is the main project.

3. Implementation processes:

The paper qusestions the implementation of FABs from three angles : the integrative efficiency of FABs , the workability of the perspectives with regard to technololgy and the dynamic process of implementation.

FAB is a cornerstone of the single european oky initiative, the principle is to define airspace portions independently of national of national boundaries constrains so as to allow for safety and efficiency gains in air triaffic services provision . Hence FAB affears both a for irpace design optimisation and service provision restructing. the obective of the paper is three fold.

1. H presents the FAB issue according to the expectations that

have been progressively attached to it.

2. it reviews experiments and competing perspectives on FAB .

3. It dis cusses implementatio proless.

RECOMMENDATION :

¨ FABs is presernted according to the expectaations . that have been progressively

attached to it .

¨ FABs reviews experiments and copeting perspectives.

¨ FABs is discussed well and there is implementation process.

NOTE :

This document presents an analysis of how functional airspace blocks could be defined, based on the analysis of past multinational initiatives, and a survey of the possible approaches which could be used.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES :

1. Expectations on FABS.

FABS have to be designed free from national boundaries con'straint to in crease safety and efficiency in Air traffic service provision. the task should be considered in regard to the general functions assigned to FABS.

2. Reviewing competing perspestives on FABS.

A minimalist approch consists of fostering service co - ordination of providers on components of service over cross-border or air space European regions by means of negotiated participation. An embryonic approch is the main project.

3. Implementation processes:

The paper qusestions the implementation of FABs from three angles : the integrative efficiency of FABs , the workability of the perspectives with regard to technololgy and the dynamic process of implementation.

FAB is a cornerstone of the single european oky initiative, the principle is to define airspace portions independently of national of national boundaries constrains so as to allow for safety and efficiency gains in air triaffic services provision . Hence FAB affears both a for irpace design optimisation and service provision restructing. the obective of the paper is three fold.

1. H presents the FAB issue according to the expectations that

have been progressively attached to it.

2. it reviews experiments and competing perspectives on FAB .

3. It dis cusses implementatio proless.

RECOMMENDATION :

¨ FABs is presernted according to the expectaations . that have been progressively

attached to it .

¨ FABs reviews experiments and copeting perspectives.

¨ FABs is discussed well and there is implementation process.

NOTE :

This document presents an analysis of how functional airspace blocks could be defined, based on the analysis of past multinational initiatives, and a survey of the possible approaches which could be used.

عدل سابقا من قبل M.EL PELTAGY_ATC14_MAN في الثلاثاء مايو 27, 2008 12:17 pm عدل 1 مرات

M.EL PELTAGY_ATC14_MAN- Silver Captian

- عدد الرسائل : 84

العمر : 37

تاريخ التسجيل : 08/05/2008

تابع مشروع التخرج

تابع مشروع التخرج

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................... LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................. SECTION 1. THE FAB ISSUE.......................................................... 1.1. FRAGMENTATION AND EXPECTATIONS................................ 1.2. DEFINING AIRSPACE BLOCKS................................................ 1.3. FUNCTIONS............................................................................... 1.4. FABS AND THE OPTIMISATION OF SERVICE......................... 1.5. FINALISING FABS...................................................................... SECTION 2. ELEMENTARY EXPERIMENTS AND PERSPECTIVES ON FABS ......................................... 2.1. PRECURSORS OF FABS........................................................... 2.2. REGIONAL EUROPEAN CENTRES.......................................... 2.3. DRAWING FABS FROM MATHEMATICAL AND STATISTICAL ALGORITHMS........................................................ 2.4. DRAWING FABS FROM AN ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE........ 2.5. THE FUTURE OF FABS............................................................. SECTION 3. IMPLEMENTATION PROCESSES............................... 3.1. FABS AND THE INTEGRATIVE EFFICIENCY........................... 3.2. WORKABILITY OF FABS........................................................... 3.3. SETTING FABS INTO MOTION................................................. RECOMENDATION .......................................................................... REFRENCES ................................................................................... | i ii 1 1 2 6 6 7 8 8 9 13 13 14 16 16 18 19 21 22 |

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Integrative efficiency on FABs ........................................... Table 2: Implementing FABs ............................................................ Table 3: setting up FABs .................................................................. | 17 18 19 |

M.EL PELTAGY_ATC14_MAN- Silver Captian

- عدد الرسائل : 84

العمر : 37

تاريخ التسجيل : 08/05/2008

تابع مشروع التخرج

تابع مشروع التخرج

1. THE FAB ISSUE

To achieve a Single European Sky for Air Traffic Services, the European Commission

proposes to implement transnational functional airspace blocks:

“The European Union Information Region shall be reconfigured into functional airspace blocks of minimum size on the basis of safety and efficiency. The borders of such functional airspace blocks do not need to coincide with national boundaries.”

(Article 5, paragraph 1, Proposal for a Regulation on the organisation and use of the airspace in the Single European Sky, submitted to the European Parliament)

How to think these airspace blocks? What should be their ultimate purpose? Which principles would help defining their boundaries?

1.1. Fragmentation and expectations

A Single European Sky was on the political agenda forty years ago. The political attempt was to create a single European provider responsible for en-route Air Traffic Services.

As it failed, the definition of routes, sectors, the military airspace and the service provision have been managed under a national rationale. Co-operation, delegation of service between states has occurred on voluntary bilateral and multilateral air treaties. Within Eurocontrol Agency, which has lacked political power, the search for consensus has prevailed, preventing bold and binding initiatives.

Such architecture has reached its limits. The liberalisation of air transport has given rise to unprecedented traffic growth that national providers have proved unable to cope with –see Performance Review Commission reports and the European Commission documents.

A key finding has been that fragmentation of airspace and service provision along national boundaries creates structural inefficiencies -sub-optimal flight routing, lack of interoperability, insufficient harmonisation of procedures. Among others, not only airspace is defined according to national boundaries but also vertically. Member States have organised differently in the definition and management of their lower and upper airspace. Impacts of their decisions on neighbouring countries have received scant attention. The European Commission has highlighted these drawbacks when considering delays:

“..many of the bottlenecks that cause delays stem from insufficient planning at the European level of national airspace design and air traffic control organisation .”

(Single European Sky)

Recently, the tragic accident of June the 30th over the lake of Constancy has reminded that national fragmentation not only caused delays but also proved a source of complication in co-ordinating Air Traffic Control operations.

Therefore both on safety and efficiency grounds, the baseline toward an integrated European management of airspace is reducing fragmentation.

However, although national boundaries are certainly not defining optimal solutions for airspace design, there is no clear view about what shall be the minimum size of a regional airspace block and what would be the associated efficiency gains. Reporting on the Single Sky European Commission proposal, the European Economic and Social Committee underlines:

“Would the reconfiguration of the upper airspace architecture bring the expected improvements with regard to routes, sectors and what would be the assessment criteria? …… in any case, will remain commercial interests that could well prevent the implementation of optimal regional functional airspace blocks.”

(European Economic and Social Committee, R/CES 312/2002 EN-RD/jg) – translation into English from the authors

1.2. Defining airspace blocks

The European Commission has commissioned three studies in year 2000, respectively on airspace design, market organisation and economic regulation. All three studies have converged on the need for re-organising the management of the European airspace alongside with the implementation of transnational airspace blocks. By freeing the organisation and the provision of ATM services from national historical and geographical constraints they expect increases in traffic control capacity, efficiency improvements and costs savings.

Each study has stressed on particular items.

The Airspace Design study refers to the concept of airspace continuum and the setting up of ‘Functional Airspace Blocks’ (FABs) which will no longer be dependent upon national boundaries. Airspace continuum is defined as:

“a coherent block of airspace designed on the basis of uniform principles and criteria. An airspace continuum will become an operating continuum if uniform airspace management procedures and safety standards combined with seamless ATS provision are applied.”

The following four elements are considered to be essential components of an Operating Airspace Continuum:

- Uniform high safety standards

- Uniform airspace design beyond national borders

- Uniform airspace management

- Seamless air traffic management (on a national and European levels).”

(Study for the European Commission on the regulation of Airspace Management

and Design)

The study advocates :

“A common Uniform Information Region (UIR) encompassing the upper airspace of the EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland and managed as a continuum would allow European planning to overcome regional bottlenecks……The European Regulator would assume ultimate design responsibility for establishing an upper airspace continuum where responsibility of the Air Traffic Service Providers (ATSPs) would be delineated by respective Upper Control Areas (UTAs) that are irrespective of national borders. The design of UTAs should be taken as a unique opportunity to establish FABs as large cross-border areas wherein control responsibility is assigned to one ATSP or a group of ATSPs…….

As an important measure it should be considered as a next step to establish FABs in regional airspace below upper FABs or separate where appropriate to solve cross border problems for medium haul intra European traffic….

At a later stage, a single Flight Information Region (FIR) Europe that encompasses lower and upper European airspace could be envisaged.”

(Study for the European Commission on the regulation of Airspace Management

and Design)

If not intently dealing with the restructuring of airspace, the two other studies –i.e. market

organisation and economic regulation – refers to the need for setting up transnational airspace blocks.

Bearing in mind the impact of future technology, the market analysis points out:

“The responsibilities, tasks and liabilities of controllers and pilots will be changed. Sectors, especially but not exclusively in upper airspace, may become significantly larger and traverse national boundaries…… In order to maximise the benefits of investment in technological development, there will be a need to enable the consolidation of airspace to allow airspace to be treated and managed as a continuum.

This requires two levels of co-operation:

(a) at the State legislative level to facilitate delegation of the provision of services in sovereign airspace

(b) at the service level provision level, to consolidate services, infrastructure, etc., in order to provide a joint service in the merged volume of airspace.”

(Study for the European Commission on Air Traffic Management (ATM) Market Organisation)

Moreover, to enable the impacts of advanced technologies, the Market Organisation study considers the scope for service provision restructuring:

“The approach to the development of transnational systems has generally been through the formation of a consortium of service providers to develop and implement the technology with the ultimate aim of providing the regional service.

One method of undertaking this type of joint service offering would be through the formation of a European Economic Interest Group (EEIG).”

(Study for the European Commission on Air Traffic Management (ATM) Market Organisation)

As for the economic regulation study, the restructuring of the upper European airspace assumes the definition of airspace zones of operational co-ordination (ZOCs) in a perspective almost similar to FABs but with an emphasis on efficiency gains as a main driver to their definition :

“They (ZOCs) are cross-border airspace blocks where increase in efficiency will stem from co-ordination between national providers… Current voluntary co-ordination such as the CHIEF project (CH for Switzerland, I for Italy, E for Spain and F for France) has proved successful. This type of embryonic operational co-operation produces important efficiency gains. Generalising and deepening such agreed co-ordination would add efficiency gains. It could rely on defining and isolating ZOCs according to a set of primary indices (location of airports, traffic complexity, and density).”

(Study for the European Commission on Economic Regulation)

In order to make ZOCs effective, the economic regulation recommends them to be associated with Pooling Resources Alliances (PRA) responsible for operating them in respect of regulatory contractual agreements based on incentives to performance:

“Co-operation occurs by means of Member States delegation of service provision to ZOCs and by involvement of national services providers in setting up Pooling Resources Alliances (PRA) schemes. In setting up a PRA, the involved service providers attached to a particular ZOC will be free to choose the appropriate form of co-ordination and restructuring (contractual relationships, Joint Ventures, creation of service provision entities). To facilitate the management and mobility of human resources, controllers allocated to ZOCs will receive additional training (European specialisation degree) and be given special status….

Co-operation can be encouraged through economic regulation : making co-operation financially attractive and non co-operation a financial disincentive…

Unit Zone Rates will be introduced and be based on Unit Service (US), quality (Delays), service level targets…

The distribution of revenues from service provision on ZOCs will be agreed between the involved Member States.”

(Study for the European Commission on Economic Regulation)

Thus, the European Commission High level group report and studies carried out later make the implementation of transnational

i.e. cross border- FABs a prerequisite for an effective Single European Sky.

As it emerges from above, several perspectives and methodologies have been put forward. But none enters into sufficient detail to allow for drawing the geographical boundaries of European FABs.

The regulation proposal on the organisation and use of airspace in the Single European Sky, submitted to the European Parliament and the Council, do not provide with much additional technical guidance, but it restricts FABs to the upper airspace and stresses on assets restructuring in service provision:

Article 3

Definitions

(i)”functional airspace block” means an airspace block of optimally

defined dimensions”

Article 4

Creation of a European Upper Flight Information Region. The division

level between upper and lower airspace shall be set at flight level 285

Article 5

Reconfiguration of the upper airspace

1. The EUIR shall be reconfigured into functional airspace blocks of minimum size on the basis of safety and efficiency. The borders of such functional airspace blocks do not need to coincide with national boundaries.

2. Functional airspace blocks shall be created to support the provision of air traffic services within area control centres responsible for an optimal size of airspace in the EUIR.

3. Functional airspace blocks shal be defined in accordance with the

procedure referred to in Article 16(2).

To achieve a Single European Sky for Air Traffic Services, the European Commission

proposes to implement transnational functional airspace blocks:

“The European Union Information Region shall be reconfigured into functional airspace blocks of minimum size on the basis of safety and efficiency. The borders of such functional airspace blocks do not need to coincide with national boundaries.”

(Article 5, paragraph 1, Proposal for a Regulation on the organisation and use of the airspace in the Single European Sky, submitted to the European Parliament)

How to think these airspace blocks? What should be their ultimate purpose? Which principles would help defining their boundaries?

1.1. Fragmentation and expectations

A Single European Sky was on the political agenda forty years ago. The political attempt was to create a single European provider responsible for en-route Air Traffic Services.

As it failed, the definition of routes, sectors, the military airspace and the service provision have been managed under a national rationale. Co-operation, delegation of service between states has occurred on voluntary bilateral and multilateral air treaties. Within Eurocontrol Agency, which has lacked political power, the search for consensus has prevailed, preventing bold and binding initiatives.

Such architecture has reached its limits. The liberalisation of air transport has given rise to unprecedented traffic growth that national providers have proved unable to cope with –see Performance Review Commission reports and the European Commission documents.

A key finding has been that fragmentation of airspace and service provision along national boundaries creates structural inefficiencies -sub-optimal flight routing, lack of interoperability, insufficient harmonisation of procedures. Among others, not only airspace is defined according to national boundaries but also vertically. Member States have organised differently in the definition and management of their lower and upper airspace. Impacts of their decisions on neighbouring countries have received scant attention. The European Commission has highlighted these drawbacks when considering delays:

“..many of the bottlenecks that cause delays stem from insufficient planning at the European level of national airspace design and air traffic control organisation .”

(Single European Sky)

Recently, the tragic accident of June the 30th over the lake of Constancy has reminded that national fragmentation not only caused delays but also proved a source of complication in co-ordinating Air Traffic Control operations.

Therefore both on safety and efficiency grounds, the baseline toward an integrated European management of airspace is reducing fragmentation.

However, although national boundaries are certainly not defining optimal solutions for airspace design, there is no clear view about what shall be the minimum size of a regional airspace block and what would be the associated efficiency gains. Reporting on the Single Sky European Commission proposal, the European Economic and Social Committee underlines:

“Would the reconfiguration of the upper airspace architecture bring the expected improvements with regard to routes, sectors and what would be the assessment criteria? …… in any case, will remain commercial interests that could well prevent the implementation of optimal regional functional airspace blocks.”

(European Economic and Social Committee, R/CES 312/2002 EN-RD/jg) – translation into English from the authors

1.2. Defining airspace blocks

The European Commission has commissioned three studies in year 2000, respectively on airspace design, market organisation and economic regulation. All three studies have converged on the need for re-organising the management of the European airspace alongside with the implementation of transnational airspace blocks. By freeing the organisation and the provision of ATM services from national historical and geographical constraints they expect increases in traffic control capacity, efficiency improvements and costs savings.

Each study has stressed on particular items.

The Airspace Design study refers to the concept of airspace continuum and the setting up of ‘Functional Airspace Blocks’ (FABs) which will no longer be dependent upon national boundaries. Airspace continuum is defined as:

“a coherent block of airspace designed on the basis of uniform principles and criteria. An airspace continuum will become an operating continuum if uniform airspace management procedures and safety standards combined with seamless ATS provision are applied.”

The following four elements are considered to be essential components of an Operating Airspace Continuum:

- Uniform high safety standards

- Uniform airspace design beyond national borders

- Uniform airspace management

- Seamless air traffic management (on a national and European levels).”

(Study for the European Commission on the regulation of Airspace Management

and Design)

The study advocates :

“A common Uniform Information Region (UIR) encompassing the upper airspace of the EU Member States, Norway and Switzerland and managed as a continuum would allow European planning to overcome regional bottlenecks……The European Regulator would assume ultimate design responsibility for establishing an upper airspace continuum where responsibility of the Air Traffic Service Providers (ATSPs) would be delineated by respective Upper Control Areas (UTAs) that are irrespective of national borders. The design of UTAs should be taken as a unique opportunity to establish FABs as large cross-border areas wherein control responsibility is assigned to one ATSP or a group of ATSPs…….

As an important measure it should be considered as a next step to establish FABs in regional airspace below upper FABs or separate where appropriate to solve cross border problems for medium haul intra European traffic….

At a later stage, a single Flight Information Region (FIR) Europe that encompasses lower and upper European airspace could be envisaged.”

(Study for the European Commission on the regulation of Airspace Management

and Design)

If not intently dealing with the restructuring of airspace, the two other studies –i.e. market

organisation and economic regulation – refers to the need for setting up transnational airspace blocks.

Bearing in mind the impact of future technology, the market analysis points out:

“The responsibilities, tasks and liabilities of controllers and pilots will be changed. Sectors, especially but not exclusively in upper airspace, may become significantly larger and traverse national boundaries…… In order to maximise the benefits of investment in technological development, there will be a need to enable the consolidation of airspace to allow airspace to be treated and managed as a continuum.

This requires two levels of co-operation:

(a) at the State legislative level to facilitate delegation of the provision of services in sovereign airspace

(b) at the service level provision level, to consolidate services, infrastructure, etc., in order to provide a joint service in the merged volume of airspace.”

(Study for the European Commission on Air Traffic Management (ATM) Market Organisation)

Moreover, to enable the impacts of advanced technologies, the Market Organisation study considers the scope for service provision restructuring:

“The approach to the development of transnational systems has generally been through the formation of a consortium of service providers to develop and implement the technology with the ultimate aim of providing the regional service.

One method of undertaking this type of joint service offering would be through the formation of a European Economic Interest Group (EEIG).”

(Study for the European Commission on Air Traffic Management (ATM) Market Organisation)

As for the economic regulation study, the restructuring of the upper European airspace assumes the definition of airspace zones of operational co-ordination (ZOCs) in a perspective almost similar to FABs but with an emphasis on efficiency gains as a main driver to their definition :

“They (ZOCs) are cross-border airspace blocks where increase in efficiency will stem from co-ordination between national providers… Current voluntary co-ordination such as the CHIEF project (CH for Switzerland, I for Italy, E for Spain and F for France) has proved successful. This type of embryonic operational co-operation produces important efficiency gains. Generalising and deepening such agreed co-ordination would add efficiency gains. It could rely on defining and isolating ZOCs according to a set of primary indices (location of airports, traffic complexity, and density).”

(Study for the European Commission on Economic Regulation)

In order to make ZOCs effective, the economic regulation recommends them to be associated with Pooling Resources Alliances (PRA) responsible for operating them in respect of regulatory contractual agreements based on incentives to performance:

“Co-operation occurs by means of Member States delegation of service provision to ZOCs and by involvement of national services providers in setting up Pooling Resources Alliances (PRA) schemes. In setting up a PRA, the involved service providers attached to a particular ZOC will be free to choose the appropriate form of co-ordination and restructuring (contractual relationships, Joint Ventures, creation of service provision entities). To facilitate the management and mobility of human resources, controllers allocated to ZOCs will receive additional training (European specialisation degree) and be given special status….

Co-operation can be encouraged through economic regulation : making co-operation financially attractive and non co-operation a financial disincentive…

Unit Zone Rates will be introduced and be based on Unit Service (US), quality (Delays), service level targets…

The distribution of revenues from service provision on ZOCs will be agreed between the involved Member States.”

(Study for the European Commission on Economic Regulation)

Thus, the European Commission High level group report and studies carried out later make the implementation of transnational

i.e. cross border- FABs a prerequisite for an effective Single European Sky.

As it emerges from above, several perspectives and methodologies have been put forward. But none enters into sufficient detail to allow for drawing the geographical boundaries of European FABs.

The regulation proposal on the organisation and use of airspace in the Single European Sky, submitted to the European Parliament and the Council, do not provide with much additional technical guidance, but it restricts FABs to the upper airspace and stresses on assets restructuring in service provision:

Article 3

Definitions

(i)”functional airspace block” means an airspace block of optimally

defined dimensions”

Article 4

Creation of a European Upper Flight Information Region. The division

level between upper and lower airspace shall be set at flight level 285

Article 5

Reconfiguration of the upper airspace

1. The EUIR shall be reconfigured into functional airspace blocks of minimum size on the basis of safety and efficiency. The borders of such functional airspace blocks do not need to coincide with national boundaries.

2. Functional airspace blocks shall be created to support the provision of air traffic services within area control centres responsible for an optimal size of airspace in the EUIR.

3. Functional airspace blocks shal be defined in accordance with the

procedure referred to in Article 16(2).

M.EL PELTAGY_ATC14_MAN- Silver Captian

- عدد الرسائل : 84

العمر : 37

تاريخ التسجيل : 08/05/2008

تابع مشروع التخرج

تابع مشروع التخرج

1.3. Functions

Mapping FABs is a not only a question of size and boundaries. The functions attached to an airspace block define at the same time what is performed for a particular area –the purpose of the airspace block- and in accordance who will manage it.

But what are the functional criteria ?

As a general meaning, functions refer to safety and efficiency rather than historical and political geography (see airspace design study p.64). But in generic terms, they do not provide with answers when it comes to operations. Nor is addressed the issue of potential trade-offs between safety and efficiency. It also refers to adjustment to future demand (traffic pattern), network effects and optimising transaction between area control centres.

These objectives can be studied in regard to the Commission market and economic regulation studies which split Air Traffic Services into four categories : airspace design (infrastructure), Air Traffic Flow Management, Air Traffic Control operations, ancillary services. Operating an airspace block will require combining the four services. In future ancillary services are likely to be provided through market forces. Therefore, they will less be a characteristic of FABs.

FABs shall be mapped as to optimised each category of service provision, and optimising means safety and efficiency criteria. Criteria shall apply to airspace design (the network of routes and sectors), to managing with traffic flows (organisation of ATFM); to Air Traffic Control operations (handling of flights).

1.4. FABs and the optimisation of service

Safety and efficiency criteria questions the adequate level of centralisation in service provision and consequently the size, number and purpose of FABs:

¨ Airspace Design : to what extent the route structure and sectorisation shall be handled centrally ? What would be the appropriate number of large airspace blocks ? Could European airspace blocks be isolated above a certain altitude –FL285 upwards (above FL300, overflights dominate)- on a European basis?

¨ ATFM : shall it be fully centralised and de-centrally run ? What would be the regional relays for Collaborative Decision-Making processes ? Should they be attached to operating airspace blocks?

¨ Air Traffic Control : the number of civil en-route ANSPs for the Eurocontrol area is 26 against 1 in the US for half the surface coverage. The number of en-routes centres is 58 (41 covering the EU) against 21 –see PRR4, April 2001. Shall airspace blocks be a tool for restructuring ATCs and ANSPs? What would be the optimal centralisation of Air Traffic Control operations?

It is not clear whether optimisation will require identical centralisation according to services and how could the centralisation levels match the mapping of FABs.

1.5. Finalising FABs

The sovereignty principle applies to Air Traffic Services provision. Even if provision can be delegated, nation states are held responsible for ensuring safety. Also charges shall not subsidise other services not related to provision.

Moving from national fragmentation to transnational FABs requires deciding upon a pathway. At the extremes FABs can either result from spontaneous voluntary member states initiatives or be centrally managed by a European entity.

In the case of voluntary bi or multilateral arrangements, incentives have to be devised so as to promote the interest of the member states to create or join in FABs -bottom up approach. At the other extreme, the fully centralised member states would comply with binding FABs mapped by a supranational authority –top down approach.

With no intent on dealing with the institutional perspective, how will FABs be regulated and what would be the relationship with national regulation and regulators? How would be organised regulation and constraints –a co-operative model based on Commission benchmarking and meetings with national regulators? What could be the meaning of a European regulator in relation to FABs?

Mapping FABs is a not only a question of size and boundaries. The functions attached to an airspace block define at the same time what is performed for a particular area –the purpose of the airspace block- and in accordance who will manage it.

But what are the functional criteria ?

As a general meaning, functions refer to safety and efficiency rather than historical and political geography (see airspace design study p.64). But in generic terms, they do not provide with answers when it comes to operations. Nor is addressed the issue of potential trade-offs between safety and efficiency. It also refers to adjustment to future demand (traffic pattern), network effects and optimising transaction between area control centres.

These objectives can be studied in regard to the Commission market and economic regulation studies which split Air Traffic Services into four categories : airspace design (infrastructure), Air Traffic Flow Management, Air Traffic Control operations, ancillary services. Operating an airspace block will require combining the four services. In future ancillary services are likely to be provided through market forces. Therefore, they will less be a characteristic of FABs.

FABs shall be mapped as to optimised each category of service provision, and optimising means safety and efficiency criteria. Criteria shall apply to airspace design (the network of routes and sectors), to managing with traffic flows (organisation of ATFM); to Air Traffic Control operations (handling of flights).

1.4. FABs and the optimisation of service

Safety and efficiency criteria questions the adequate level of centralisation in service provision and consequently the size, number and purpose of FABs:

¨ Airspace Design : to what extent the route structure and sectorisation shall be handled centrally ? What would be the appropriate number of large airspace blocks ? Could European airspace blocks be isolated above a certain altitude –FL285 upwards (above FL300, overflights dominate)- on a European basis?

¨ ATFM : shall it be fully centralised and de-centrally run ? What would be the regional relays for Collaborative Decision-Making processes ? Should they be attached to operating airspace blocks?

¨ Air Traffic Control : the number of civil en-route ANSPs for the Eurocontrol area is 26 against 1 in the US for half the surface coverage. The number of en-routes centres is 58 (41 covering the EU) against 21 –see PRR4, April 2001. Shall airspace blocks be a tool for restructuring ATCs and ANSPs? What would be the optimal centralisation of Air Traffic Control operations?

It is not clear whether optimisation will require identical centralisation according to services and how could the centralisation levels match the mapping of FABs.

1.5. Finalising FABs

The sovereignty principle applies to Air Traffic Services provision. Even if provision can be delegated, nation states are held responsible for ensuring safety. Also charges shall not subsidise other services not related to provision.

Moving from national fragmentation to transnational FABs requires deciding upon a pathway. At the extremes FABs can either result from spontaneous voluntary member states initiatives or be centrally managed by a European entity.

In the case of voluntary bi or multilateral arrangements, incentives have to be devised so as to promote the interest of the member states to create or join in FABs -bottom up approach. At the other extreme, the fully centralised member states would comply with binding FABs mapped by a supranational authority –top down approach.

With no intent on dealing with the institutional perspective, how will FABs be regulated and what would be the relationship with national regulation and regulators? How would be organised regulation and constraints –a co-operative model based on Commission benchmarking and meetings with national regulators? What could be the meaning of a European regulator in relation to FABs?

M.EL PELTAGY_ATC14_MAN- Silver Captian

- عدد الرسائل : 84

العمر : 37

تاريخ التسجيل : 08/05/2008

تابع مشروع التخرج

تابع مشروع التخرج

2. ELEMENTARY EXPERIMENTS AND PERSPECTIVES ON FABs

Co-operation among service providers, delegation of service provision, European wide projects managed under the auspices Eurocontrol have been in place for long. The section gives account of some of them from public sources. Other approaches on airspace blocks are also singled out.

2.1. Precursors of FABs

Multinational and multi-centre co-operative projects aim at rationalising sectorisation and creating additional capacity. The most important ones relate to developing Trans-European projects such as “Highways of Sky”. Among them, the Area South of Europe roject known as CHIEF –standing for Switzerland, Italy, Spain and France- makes up a regional airspace block from an airspace design restructuring perspective.

CHIEF looks for outcomes similar to airspace blocks in regard to the optimisation of airspace design. This form of co-operation does not entail the transfer of Air Traffic Control assets or changes in delegation of service. It simply requires a joint-decision mechanism on key items in order to increase efficiency in the system.

Generalising it to more binding cross-border re-sectorisation could further enhance the co-operative approach. Mapping of FABs would concentrate on national boundaries and critical nodes from a fresh look at the current situation. To make it workable revenue would be shared by providers according to a satisfactory allocative mechanism between parties.

Skyguide has advocated the scenario of generalising co-operation:

“Overambitious plans will unavoidably lead to failures, possibly endangering not only individuals elements of the Single European Sky, but the concept as a whole.

….. The key to a successful FAB is related to the process applied for the design of the concept. Work must begin with an operational focus, with the view of defining the most technically sensible solution.

…. As explained above, the traditional way of organising ANS has been to build sectors closely following national boundaries. Such an approach will unavoidably result in an inefficient ATC system, in particular where crossing points are located close to sectors boundaries, depriving Air Traffic Controllers of the required distance to anticipate conflict resolution actions. The remedy in an airspace structure based upon political borders is to distort the natural flow of air traffic in such a way as to move crossing points away from the limits of controlled sectors. Airspace users are penalised because the unnecessary longer distances to fly.

The most logical first step in the design of FAB would be start with a blank sheet of paper and to draw natural flows of traffic passing through a given area with reference whatsoever to national boundaries. From that process, the broad contours of a logical operational envelope will emerge, which will become the outside limits of a FAB.”

As a first step, such co-operative mechanism could apply to FABs upper airspace. It would emphasise the importance of a full respect of national sovereignty with practical and realistic solutions. Later could be implemented more radical changes.

2.2. Regional European centres

Another approach is to consider airspace blocks from an ACC perspective. A control centre is set up to handle a European regional airspace block under multilateral agreements.

Three examples of European regional en-route centres provide for examples: Maastricht,

CEATS and NUAC

Maastricht UAC

The Maastricht UAC illustrates an evolving development of the regional FAB concept.

At start in 1964 Belgium was the first Member State to delegate the en-route control of its upper airspace –above FL195- to Eurocontrol, to begin with at Brussels National airport and later in 1972 at the Maastricht Centre. Two years later, the Centre was entrusted control over the Northern German upper airspace - above FL245. In 1986, the Netherlands agreed to delegate to Maastricht provision of service for its upper airspace -above FL300. In 1993, the Centre was given the responsibility for en-route control of traffic flows above FL245 with a reorganisation of the Belgium upper and lower airspace. In addition the Maastricht Centre hosts a DFS military control unit.

Dealing with complex flows –ascending and descending phases, Maastricht has evolved towards a more upper airspace control centre but without having reached the flight level 285or 295 separation which might be a mark for qualifying for FABs.

The organisation tends also to reproduce national boundaries. Maastricht is divided up into the Hanover sector group, the Brussels sector group, the Delta-Costal sector group. In other words, control carries on being based on national consideration and revenues are split in proportion to traffic handled nationally –Luxembourg (1.06%) ; Belgium (34.39%) ; Germany (43.78%) ; The Netherlands (20.77%).

In short Maastricht –except for German adhesion- materialises the sensible combination of airspace portions that are too small to be efficiently run on a strict national basis. It is a transnational arrangement resulting from a ‘Minimum Efficient Size’ rationale rather than an attempt of creating a particular centre dedicated to manage an enlarged airspace block and/or specialising in high level flights service provision.

Central European Air Traffic Services UAC

CEATS has been made official by the signature of a multilateral agreement on 27 June 1997. It a a new common Upper Area Control Centre which covers a large part of the East European airspace: Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy (the northern part which consists of the sectors of Padova ACC), Slovakia and Slovenia. The regional airspace block is defined vertically above FL285/FL290, which in itself makes it coherent with a Transeuropean network, and management of overflights.

Eurocontrol stresses the expected benefits from CEATS and details the technical tools to

achieve that end:

“to enable an increase in capacity and a decrease in the cost of services per unit while maintaining the flight safety by :

- uniform airspace procedures

- optimal sectorisation regardless to national border

- direct routings

- uniform and cost recovery implementation of new technologies

and concepts

- sharing of resources.

CEATS is scheduled to be operational by 2007-2010. Rather than a ‘big bang’ approach with duplication of investment and sudden switch to the new Centre, a step by step approach has been prefered:

“the migration from the current situation to the target situation will be through several stages where the current centres are gradually transformed to a ‘virtual centre’. Once this is achieved, it should be a ‘simple’ matter of relocating resources to rationalise the number of centres in the area.

The ‘virtual centre’ involves the gradual harmonisation and where possible, integration or unification of :

- regulation, including licensing and certification ;

- airspace management, including intra-centre, inter-centre and

civil/military co-ordination ;

- systems, including surveil ance data processing, flight data

processing systems and HMI ;

- human resources management, including training and working

conditions

(CEATS presentation background)

Co-operation among service providers, delegation of service provision, European wide projects managed under the auspices Eurocontrol have been in place for long. The section gives account of some of them from public sources. Other approaches on airspace blocks are also singled out.

2.1. Precursors of FABs

Multinational and multi-centre co-operative projects aim at rationalising sectorisation and creating additional capacity. The most important ones relate to developing Trans-European projects such as “Highways of Sky”. Among them, the Area South of Europe roject known as CHIEF –standing for Switzerland, Italy, Spain and France- makes up a regional airspace block from an airspace design restructuring perspective.

CHIEF looks for outcomes similar to airspace blocks in regard to the optimisation of airspace design. This form of co-operation does not entail the transfer of Air Traffic Control assets or changes in delegation of service. It simply requires a joint-decision mechanism on key items in order to increase efficiency in the system.

Generalising it to more binding cross-border re-sectorisation could further enhance the co-operative approach. Mapping of FABs would concentrate on national boundaries and critical nodes from a fresh look at the current situation. To make it workable revenue would be shared by providers according to a satisfactory allocative mechanism between parties.

Skyguide has advocated the scenario of generalising co-operation:

“Overambitious plans will unavoidably lead to failures, possibly endangering not only individuals elements of the Single European Sky, but the concept as a whole.

….. The key to a successful FAB is related to the process applied for the design of the concept. Work must begin with an operational focus, with the view of defining the most technically sensible solution.

…. As explained above, the traditional way of organising ANS has been to build sectors closely following national boundaries. Such an approach will unavoidably result in an inefficient ATC system, in particular where crossing points are located close to sectors boundaries, depriving Air Traffic Controllers of the required distance to anticipate conflict resolution actions. The remedy in an airspace structure based upon political borders is to distort the natural flow of air traffic in such a way as to move crossing points away from the limits of controlled sectors. Airspace users are penalised because the unnecessary longer distances to fly.

The most logical first step in the design of FAB would be start with a blank sheet of paper and to draw natural flows of traffic passing through a given area with reference whatsoever to national boundaries. From that process, the broad contours of a logical operational envelope will emerge, which will become the outside limits of a FAB.”

As a first step, such co-operative mechanism could apply to FABs upper airspace. It would emphasise the importance of a full respect of national sovereignty with practical and realistic solutions. Later could be implemented more radical changes.

2.2. Regional European centres

Another approach is to consider airspace blocks from an ACC perspective. A control centre is set up to handle a European regional airspace block under multilateral agreements.

Three examples of European regional en-route centres provide for examples: Maastricht,

CEATS and NUAC

Maastricht UAC

The Maastricht UAC illustrates an evolving development of the regional FAB concept.

At start in 1964 Belgium was the first Member State to delegate the en-route control of its upper airspace –above FL195- to Eurocontrol, to begin with at Brussels National airport and later in 1972 at the Maastricht Centre. Two years later, the Centre was entrusted control over the Northern German upper airspace - above FL245. In 1986, the Netherlands agreed to delegate to Maastricht provision of service for its upper airspace -above FL300. In 1993, the Centre was given the responsibility for en-route control of traffic flows above FL245 with a reorganisation of the Belgium upper and lower airspace. In addition the Maastricht Centre hosts a DFS military control unit.

Dealing with complex flows –ascending and descending phases, Maastricht has evolved towards a more upper airspace control centre but without having reached the flight level 285or 295 separation which might be a mark for qualifying for FABs.

The organisation tends also to reproduce national boundaries. Maastricht is divided up into the Hanover sector group, the Brussels sector group, the Delta-Costal sector group. In other words, control carries on being based on national consideration and revenues are split in proportion to traffic handled nationally –Luxembourg (1.06%) ; Belgium (34.39%) ; Germany (43.78%) ; The Netherlands (20.77%).

In short Maastricht –except for German adhesion- materialises the sensible combination of airspace portions that are too small to be efficiently run on a strict national basis. It is a transnational arrangement resulting from a ‘Minimum Efficient Size’ rationale rather than an attempt of creating a particular centre dedicated to manage an enlarged airspace block and/or specialising in high level flights service provision.

Central European Air Traffic Services UAC

CEATS has been made official by the signature of a multilateral agreement on 27 June 1997. It a a new common Upper Area Control Centre which covers a large part of the East European airspace: Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy (the northern part which consists of the sectors of Padova ACC), Slovakia and Slovenia. The regional airspace block is defined vertically above FL285/FL290, which in itself makes it coherent with a Transeuropean network, and management of overflights.

Eurocontrol stresses the expected benefits from CEATS and details the technical tools to

achieve that end:

“to enable an increase in capacity and a decrease in the cost of services per unit while maintaining the flight safety by :

- uniform airspace procedures

- optimal sectorisation regardless to national border

- direct routings

- uniform and cost recovery implementation of new technologies

and concepts

- sharing of resources.

CEATS is scheduled to be operational by 2007-2010. Rather than a ‘big bang’ approach with duplication of investment and sudden switch to the new Centre, a step by step approach has been prefered:

“the migration from the current situation to the target situation will be through several stages where the current centres are gradually transformed to a ‘virtual centre’. Once this is achieved, it should be a ‘simple’ matter of relocating resources to rationalise the number of centres in the area.

The ‘virtual centre’ involves the gradual harmonisation and where possible, integration or unification of :

- regulation, including licensing and certification ;

- airspace management, including intra-centre, inter-centre and

civil/military co-ordination ;

- systems, including surveil ance data processing, flight data

processing systems and HMI ;

- human resources management, including training and working

conditions

(CEATS presentation background)

M.EL PELTAGY_ATC14_MAN- Silver Captian

- عدد الرسائل : 84

العمر : 37

تاريخ التسجيل : 08/05/2008

تابع مشروع التخرج

تابع مشروع التخرج

NUAC

The NUAC project corresponds to the creation of a quasi European Nordic regional FAB,

even if it does comply with the European FIR principle. It covers the upper airspace of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

There are particular characteristics attached to the Nordic FAB project that have probably made it easier to get commitment.

In the first place, one Nordic Airline Company dominates over the Nordic airspace. SAS is the first buyer of ATS in Sweden (44%), in Norway (42%), in Denmark (35%). SAS has hubs in Copenhagen and Stockholm, and the main airline company at Oslo. Therefore, there is overall balance between the monopoly power of the ANSPs, the suppliers, and the purchasing power of the main user of service, the buyer. Under the circumstances, the emergence of a collaborative environment between suppliers and buyer is more likely. The situation is unique in Europe.

A second characteristic is the civil-military interface. The Nordic region has airspace availability for making the military issue less complex when mapping the FAB.

For example,

in the case of Sweden, the drawing of routes and sectors dedicated to the military has been decided in the less dense civil traffic areas. Besides, in Sweden, civil and the military have been subject to integration –quite similar to Switzerland and Germany. In 1966, they were two separate ANSPs. It took about ten years to integrate both systems with operational units in 1978. The governing principle has been a clear division of responsibilities. The Luftfartverket (LFV), the Swedish Civil Aviation Administration, is responsible for peace time manning of all ATS units. The Swedish Armed Forces (SAF) will take over at times of tension or war, managing the LFV staff. Formal agreements between LFV and SAF have been signed. They detail the co-ordination decision-making mechanism, the sharing of costs and financing of investments. The staffing of LFV numbers 1200, 20% of controllers working at military airports, all controllers being in capacity to handle both civil and military traffic. The military itself makes use of civil airports. Hence controllers are used to controlling military flights. Also, as in other countries, the military have reserved training airspace blocks but clearance is given on the basis of meeting civil needs.

The third characteristic of the NUAC experiment is the nature of the restructuring process. The NUAC project is not so much the instrument for change as the consequence of the need for change. Sweden has given the impetus. In 1998, new direct routes were introduced which have received the support of politicians. Attempts to think how to increase and better manage capacity were made. So far Sweden has had three ACCs, Malmِ, Stockholm and Sundswall, each in charge of a FIR. Different options were debated so as to determine whether one or two Centres would be most appropriate. Apparently, from interviews at the LFV, the choice of two centres has rather been made on political than technical grounds. NUAC is itself in line with the Single European Sky perspective. It introduces separation between lower and upper airspace at FL285, and it promotes restructuring. It leads to a two centres option, one in Malmِ for en-route upper airspace control, the other one in Stockholm for lower airspace. The efficiency gains of the operation seem not so much lying in less costly co-ordination or better direct routing but in re-sectorisation at the borders in the North as in the South of the Nordic airspace. Sweden with Denmark are leading the NUAC initiative. It is phased that the upper Swedish airspace will first be separate and service provision restructured with two ACCs in 2004. Then Denmark will join in and subsequently Norway and Finland, NUAC being scheduled to be operational in year 2006.

The fourth characteristic is that NUAC does not intend to reproduce the Maastricht organisation with respective nationals controlling national airspace. The aim is to create a transnational management of the upper airspace Nordic Region, revenues being allocated to a likely NUAC private entity of which member states would be shareholders.

Representatives at the LFV insist on two basic processes and overcoming one hurdle to a successful transnational FAB restructuring : the involvement of all parties and in particular the controllers; a sustained political will and commitment; the hurdle being the regulatory framework. The predicament is to see NUAC getting bogged down in complying with different national regulatory frameworks. Even if a joint regional regulatory Committee can be studied, the idea of a regional regulator might be more appropriate.

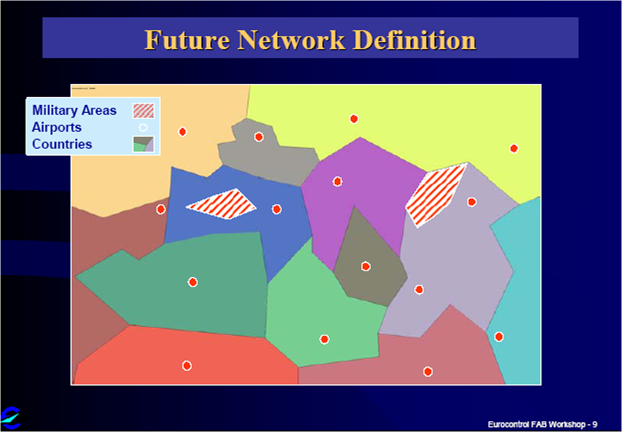

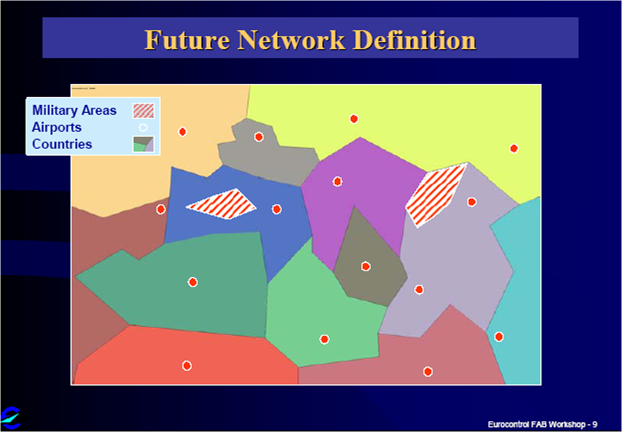

2.3. Drawing FABs from mathematical and statistical algorithms

Mathematical and statistical algorithms are used to optimising airspace design and drawing FABs. Work currently carried out at the Eurocontrol Experimental Centre on HADES (airspace design) and COCA (complexity indicators) helps drawing FABs from such perspective.

Under the HADES approach, a FAB is considered an optimised envelope where continuity of airspace and routes are required. The starting point is the demand side. Airline traffic flows with minima of traffic between city pairs are computed. Then, an optimised network of routes is drawn which seeks the maximum use of airspace. Constraints on military areas, Air Traffic Control Centres can be included in the modelling. The sectorisation outcome stems from routes and traffic flows.

Sectorisation is based on the creation of airspace volume units. The frontiers of the airspace units are drawn according to city pairs and crossing points. Then they are assembled into sectors so as to maximise a fitness function, which takes into account workload control, and complexity indicators. The function allows for a sector not to exceed a particular workload threshold and ensure a minimum flying distance in it. The last step consists of going from sectors to coherent FABs and European ACCs taking account of reactionary impacts between sectors.

Such mathematical algorithm does not draw sectors, FABs, from the existing situation. In this regard, it is easy to illustrate that the outcome of the process does not match the division of the European airspace along the existing national boundaries, even if the results can be subject to debate as the FABs frontiers depends very much on parameters values.

The algorithm can also be used in different configurations. It can apply to an existing set of routes and network and/or to existing sectorisation.

The interest of the abstract mathematical approach is to propose a number of coherent FABs from an optimised airspace design perspective. The results of simulation can then be compared to practical FABs options or else, from existing airspace design. From that interaction FABs can be drawn and might prove a power tool for discussing ANSPs FABs

proposals.

2.4. Drawing FABs from an economic perspective

From an economic perspective FABs are tools for service provision restructuring. FABs are looked at as economic entities to which are attached revenues and management of assets. They are mapped so as to maximise economic efficiency –maximising economies of scale, minimising the costs of co-ordination, rationalising assets.

For a given airspace block, service provision has cost function that varies according to the level, the density and complexity of traffic. If cost-related a charging mechanism shall allow more revenues to complex areas where control is made more difficult and requires additional manning. Besides congested areas where delays are high shall be the focus of attention as they raise the issue of quality of service. Investment shall therefore be allocated to improve level and quality of service.

A starting point is categorising airspace with the help of economic related indicators on complexity, level of service, delays, and revenues. Large airspace portions can then be drawn congruent with the economic indicators.

For example, and although of limitation as FABs are only thought as clusters of countries, economic study illustrates that a single charging mechanism including a financial compensation to airline companies when they experience delays could apply uniformly to group of countries:

The data and econometric analysis suggest that such outcome

(i.e. a new unit rate profile consistent with European uniform financial compensation on delays) could have been achieved by grouping countries into three clusters

(i.e. economic FABs): small national airspace portions at crossroads of most frequently European flown routes (The Benelux and Switzerland); peripheral countries (Nordic countries, Ireland, Portugal and Austria); large European core countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK)

Hence, instead of national charging mechanism, remuneration for provision of service can be based on transfrontier airspace blocks. The overriding principle is to make charges coherent with complexity in service provision and search for increases in capacity and efficiency gains. These transfrontier airspace blocks define FABs.

Instead of airspace nation states, the economic perspective can apply to sectors. The uniform charging mechanism applies to cluster of sectors, which are comparable from an economic perspective. These clusters are economic FABs, but the latter are no longer in the limits of an airspace continuum.

2.5. The future of FABs

The creation of FABs is a dynamic process. FABs are currently studied and will be drawn

from existing available technology, taking on board future equipment developments. It pictures an evolutionary model, which seeks safety and efficiency gains by reproducing the traditional vision of service provision. Based on experiments in progress (CEATS, NUAC) the evolutionary model is likely to necessitate at least several years to completion.

A key issue is to consider the evolutionary European strategy in the light of a complete rethink of service provision. In particular what might be the impact on FABs of the technological quantum jump proposed by Boeing and to a certain extent EADS?

Although not completely new the approach is voluntarily revolutionary as it introduces a radical new vision. The vision is based on satellite communications and positioning. It contends a move of Air Traffic Control from ground facilities to aircraft cockpit:

The NUAC project corresponds to the creation of a quasi European Nordic regional FAB,

even if it does comply with the European FIR principle. It covers the upper airspace of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

There are particular characteristics attached to the Nordic FAB project that have probably made it easier to get commitment.

In the first place, one Nordic Airline Company dominates over the Nordic airspace. SAS is the first buyer of ATS in Sweden (44%), in Norway (42%), in Denmark (35%). SAS has hubs in Copenhagen and Stockholm, and the main airline company at Oslo. Therefore, there is overall balance between the monopoly power of the ANSPs, the suppliers, and the purchasing power of the main user of service, the buyer. Under the circumstances, the emergence of a collaborative environment between suppliers and buyer is more likely. The situation is unique in Europe.

A second characteristic is the civil-military interface. The Nordic region has airspace availability for making the military issue less complex when mapping the FAB.

For example,

in the case of Sweden, the drawing of routes and sectors dedicated to the military has been decided in the less dense civil traffic areas. Besides, in Sweden, civil and the military have been subject to integration –quite similar to Switzerland and Germany. In 1966, they were two separate ANSPs. It took about ten years to integrate both systems with operational units in 1978. The governing principle has been a clear division of responsibilities. The Luftfartverket (LFV), the Swedish Civil Aviation Administration, is responsible for peace time manning of all ATS units. The Swedish Armed Forces (SAF) will take over at times of tension or war, managing the LFV staff. Formal agreements between LFV and SAF have been signed. They detail the co-ordination decision-making mechanism, the sharing of costs and financing of investments. The staffing of LFV numbers 1200, 20% of controllers working at military airports, all controllers being in capacity to handle both civil and military traffic. The military itself makes use of civil airports. Hence controllers are used to controlling military flights. Also, as in other countries, the military have reserved training airspace blocks but clearance is given on the basis of meeting civil needs.

The third characteristic of the NUAC experiment is the nature of the restructuring process. The NUAC project is not so much the instrument for change as the consequence of the need for change. Sweden has given the impetus. In 1998, new direct routes were introduced which have received the support of politicians. Attempts to think how to increase and better manage capacity were made. So far Sweden has had three ACCs, Malmِ, Stockholm and Sundswall, each in charge of a FIR. Different options were debated so as to determine whether one or two Centres would be most appropriate. Apparently, from interviews at the LFV, the choice of two centres has rather been made on political than technical grounds. NUAC is itself in line with the Single European Sky perspective. It introduces separation between lower and upper airspace at FL285, and it promotes restructuring. It leads to a two centres option, one in Malmِ for en-route upper airspace control, the other one in Stockholm for lower airspace. The efficiency gains of the operation seem not so much lying in less costly co-ordination or better direct routing but in re-sectorisation at the borders in the North as in the South of the Nordic airspace. Sweden with Denmark are leading the NUAC initiative. It is phased that the upper Swedish airspace will first be separate and service provision restructured with two ACCs in 2004. Then Denmark will join in and subsequently Norway and Finland, NUAC being scheduled to be operational in year 2006.

The fourth characteristic is that NUAC does not intend to reproduce the Maastricht organisation with respective nationals controlling national airspace. The aim is to create a transnational management of the upper airspace Nordic Region, revenues being allocated to a likely NUAC private entity of which member states would be shareholders.

Representatives at the LFV insist on two basic processes and overcoming one hurdle to a successful transnational FAB restructuring : the involvement of all parties and in particular the controllers; a sustained political will and commitment; the hurdle being the regulatory framework. The predicament is to see NUAC getting bogged down in complying with different national regulatory frameworks. Even if a joint regional regulatory Committee can be studied, the idea of a regional regulator might be more appropriate.

2.3. Drawing FABs from mathematical and statistical algorithms

Mathematical and statistical algorithms are used to optimising airspace design and drawing FABs. Work currently carried out at the Eurocontrol Experimental Centre on HADES (airspace design) and COCA (complexity indicators) helps drawing FABs from such perspective.

Under the HADES approach, a FAB is considered an optimised envelope where continuity of airspace and routes are required. The starting point is the demand side. Airline traffic flows with minima of traffic between city pairs are computed. Then, an optimised network of routes is drawn which seeks the maximum use of airspace. Constraints on military areas, Air Traffic Control Centres can be included in the modelling. The sectorisation outcome stems from routes and traffic flows.

Sectorisation is based on the creation of airspace volume units. The frontiers of the airspace units are drawn according to city pairs and crossing points. Then they are assembled into sectors so as to maximise a fitness function, which takes into account workload control, and complexity indicators. The function allows for a sector not to exceed a particular workload threshold and ensure a minimum flying distance in it. The last step consists of going from sectors to coherent FABs and European ACCs taking account of reactionary impacts between sectors.

Such mathematical algorithm does not draw sectors, FABs, from the existing situation. In this regard, it is easy to illustrate that the outcome of the process does not match the division of the European airspace along the existing national boundaries, even if the results can be subject to debate as the FABs frontiers depends very much on parameters values.

The algorithm can also be used in different configurations. It can apply to an existing set of routes and network and/or to existing sectorisation.

The interest of the abstract mathematical approach is to propose a number of coherent FABs from an optimised airspace design perspective. The results of simulation can then be compared to practical FABs options or else, from existing airspace design. From that interaction FABs can be drawn and might prove a power tool for discussing ANSPs FABs

proposals.

2.4. Drawing FABs from an economic perspective

From an economic perspective FABs are tools for service provision restructuring. FABs are looked at as economic entities to which are attached revenues and management of assets. They are mapped so as to maximise economic efficiency –maximising economies of scale, minimising the costs of co-ordination, rationalising assets.

For a given airspace block, service provision has cost function that varies according to the level, the density and complexity of traffic. If cost-related a charging mechanism shall allow more revenues to complex areas where control is made more difficult and requires additional manning. Besides congested areas where delays are high shall be the focus of attention as they raise the issue of quality of service. Investment shall therefore be allocated to improve level and quality of service.

A starting point is categorising airspace with the help of economic related indicators on complexity, level of service, delays, and revenues. Large airspace portions can then be drawn congruent with the economic indicators.

For example, and although of limitation as FABs are only thought as clusters of countries, economic study illustrates that a single charging mechanism including a financial compensation to airline companies when they experience delays could apply uniformly to group of countries:

The data and econometric analysis suggest that such outcome

(i.e. a new unit rate profile consistent with European uniform financial compensation on delays) could have been achieved by grouping countries into three clusters

(i.e. economic FABs): small national airspace portions at crossroads of most frequently European flown routes (The Benelux and Switzerland); peripheral countries (Nordic countries, Ireland, Portugal and Austria); large European core countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK)

Hence, instead of national charging mechanism, remuneration for provision of service can be based on transfrontier airspace blocks. The overriding principle is to make charges coherent with complexity in service provision and search for increases in capacity and efficiency gains. These transfrontier airspace blocks define FABs.

Instead of airspace nation states, the economic perspective can apply to sectors. The uniform charging mechanism applies to cluster of sectors, which are comparable from an economic perspective. These clusters are economic FABs, but the latter are no longer in the limits of an airspace continuum.

2.5. The future of FABs

The creation of FABs is a dynamic process. FABs are currently studied and will be drawn

from existing available technology, taking on board future equipment developments. It pictures an evolutionary model, which seeks safety and efficiency gains by reproducing the traditional vision of service provision. Based on experiments in progress (CEATS, NUAC) the evolutionary model is likely to necessitate at least several years to completion.

A key issue is to consider the evolutionary European strategy in the light of a complete rethink of service provision. In particular what might be the impact on FABs of the technological quantum jump proposed by Boeing and to a certain extent EADS?

Although not completely new the approach is voluntarily revolutionary as it introduces a radical new vision. The vision is based on satellite communications and positioning. It contends a move of Air Traffic Control from ground facilities to aircraft cockpit:

M.EL PELTAGY_ATC14_MAN- Silver Captian

- عدد الرسائل : 84

العمر : 37

تاريخ التسجيل : 08/05/2008

تابع مشروع التخرج

تابع مشروع التخرج

3. IMPLEMENTATION PROCESSES

Section 1 and 2 have reviewed the definitions, experiments and perspectives in relation to FABs. The following section discusses the issue of implementation. A three-step analysis is proposed. Rather than finding outcomes the analysis attempts to develop viewpoints that could be worth considering before mapping FABs.

In the first instance, FABs are looked at in relation to the objectives of reducing fragmentation, restructuring airspace and service provision. The experiments and perspectives are gauged according to their likely consequences on the different services (optimisation of Airspace design, of ATFM, of Air Traffic Control operations). The consequences have been defined as integrative efficiency. It underlines the fact that optimising services can necessitate a more or less integrative approach between providers and that the end result might be more or less efficiency.

In the second place, as FABs’ may require lower or greater involvement from ANSPs, national and European institutions, the issue is about how realistic can be the implementation. Hence workability shall be considered in regard to technology certainty, political feasibility, economic efficiency.

Finally, the definition of an operational process is addressed. How to set it into motion is the focus of the final part of the section. It discusses centralisation versus de-centralisation, bottom-up versus top-down approach.

3.1. FABs and the integrative efficiency

The integrative efficiency is given by service according to the level of integration that the

experiments and perspectives necessitate.

The main perspectives to create FABs reads as follows: the co-operative CHIEF + model; the creation of European UAC such as NUAC; the drawing of FABs from a blank sheet taking into account considerations on traffic flows, routes, complexity; the drawing of FABs from an economic perspective; the revolutionary perspective.

The following table summarises likely outcomes of different perspectives. For example, the CHIEF+ co-operation project does not require a high degree of integration. Neighbour providers at cross-border locations can remodel airspace design. From that remodelling ATC operations can be handled by joint venture business types or consortium. At the other extreme, the revolutionary approach based on satellite and new ground facilities would require the higher degree of integration. It would mean thinking the European future in relationship with the US, new practices in considering flow management and presumably the creation of a new supranational entity to manage en-route services.

For example, a mix between the algorithm an economic perspective can be thought of: the optimisation of the sectorisation from a traffic flow perspective will result in FABs. Each FAB will then be considered as the summation of sectors that belongs to defined economic clusters. Each charging regime on FABs would then adjust accordingly.

The integration process can also be uneven when dealing with services.

For example, a possibility is to have Airspace designed defined from a European perspective. But it would not necessarily entail a particular level of integration of service providers. The providers could just adapt their operations to new routes and airspace corridors. On the other hand they can also merge several of their ACCs into one creating by then a high degree of integration.

The issue is therefore to what extent integration at the European level to optimising services will bring about the expected efficiency gains and at what cost: should FABs in the first place deal with particular nodes in the ATM network or should the starting point be more ambitious? Can airspace design be run independently with national and European initiatives at the same time? How to take into account reactionary effects in the network? By the same token, should charging regimes be differentiated according to FABs? Can FABs be managed and run independently?

3.2. Workability of FABs

Implementing FABs raise inevitably the workability issue. Of course the more ambitious and far reaching are the plans the more the uncertainty of the outcome. Here workability of FABs is assessed considering the technology, political and economics aspects.

Table 2: Implementing FABs